By Eric Gaus, Chief Economist, and Sarah Martin, Associate Forecasting Director

The policy announcements on Liberation Day marked a significant moment of economic and political disruption, introducing new challenges for the construction industry. The financial market reaction reflects the broader macroeconomic cost of increased policy uncertainty surrounding recent trade decisions. Our project planning data through March show signs of slowing in the planning process, but not quite the planning volume. Taken together these data points suggest that due to the increased uncertainty the construction sector will have a rocky 2025 despite the promising circumstances with which we started the year.

The construction industry came roaring into 2025 on the back of large government investments in infrastructure (IIJA) and industrial policy (CHIPS act). Further acceleration came from outsized private sector investment in data centers to support cloud and AI technology. The initial tariff of February and March introduced some uncertainty, but nothing too surprising. April 2nd changed all of that.

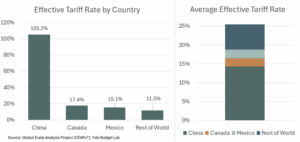

While the initial policy actions, both foreign and domestic, created uncertainty and were met with communication challenges, they were anticipated and digestible. The rollout of reciprocal tariffs featured many breakdowns in communication and resulted in much higher effective tariff rate than most economists expected. Financial markets went on a two-week roller coaster as clarifications, revisions, and reprieves were issued. The situation has calmed down, but the unease is palpable.

Uncertainty has a chilling effect on economic activity and even the relatively benign levels we saw in the first quarter impacted the data. Real-time measures of Q1 GDP were less than 1%, the stock market was moving sideways, and our measures of project planning suggested delays to timelines. Construction projects were still entering the queue at a reasonable rate, but the line was moving more slowly. The worry now is that trepidation may transition into panic as the implementation of trade policy comes into effect.

As it stands, the effective tariff rate on US imports is approximately 25-30% with the effective rate on construction goods a few percentage points higher. Most of that comes from the steel and aluminum tariffs and the outsized tariff rate on Chinese products. The economic literature estimates that overall economic inflation should increase about 0.1 ppt for every 1 ppt increase in the effective tariff rate. This implies that overall inflation should increase 2.5 to 3 percent over the next year relative to the pre-Trump tariff regime. The impact on construction costs is about 0.5 to 0.75 ppt higher than the overall inflation rate due to the mix of imported goods relative to domestic goods and labor.

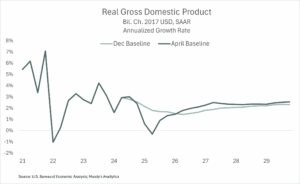

Higher effective tariff rates are also associated with lower economic growth. The estimates for that are approximately 0.05 to 0.07 ppt decline in real GDP growth for every 1 ppt increase in the effective tariff. That implies GDP growth should be roughly 1.25 to 1.5 percent slower than the pre-Trump tariff regime. Indeed, our current baseline for 2025 real GDP growth is almost 1 percent slower than the last vintage.

While these rough estimates are a useful frame of reference, we should be aware that the estimates come from studies where the variation in tariff rates was small and the level of tariffs were low. The new regime is neither low level nor a small change. Therefore, we expect that there is a significant chance that these estimates, while grounded in empirical evidence, might prove to be wrong.

For now, we are taking a cautious approach to adjusting our forecast. What the overall impact of the long-run policy looks like, positive or negative, the current uncertainty is enough to lower our forecasts across the board. Our tariff assumption is a 17.5% effective tariff in Q2, which reflects a belief of a de-escalation of tensions with China. This is followed by a gradual unwind of tariffs through mid-2026 to a stable 5% effective tariff rate. The likelihood of more forecast revisions is high as we start to get more clarity around the path of future policy.

Construction Outlook

Dodge’s revised macroeconomic assumptions carry significant near-term implications for construction, though impacts will vary by sector. Nonbuilding starts will be least affected, buoyed by infrastructure law funding in the near-term. In contrast, residential construction—highly sensitive to interest rates—will face mounting challenges in 2025 due to elevated mortgage rates and strained household budgets. Builders will also feel pressure from rising material costs and labor shortages. Nonresidential building starts are likely to soften amid broader economic uncertainty, particularly in commercial and manufacturing sectors tied closely to GDP. Institutional construction may see localized weakness as federal funding tightens, though megaprojects breaking ground early in the year should provide some offset.

The Dodge Momentum Index—which tracks early planning for nonresidential projects under $500 million, excluding manufacturing and transportation—gained steady ground in late 2024, typically signaling stronger construction activity by late 2025 or early 2026. However, rising uncertainty around tariffs may lead owners and developers to delay planning decisions, limiting how much of that momentum translates into actual spending in the near term. The median number of months it’s taking nonresidential projects (<$500M) to move from planning to start increased from 16 to 19 months in the first quarter of 2025 and that trend is likely to worsen throughout the rest of this year. Increased uncertainty around material prices and fiscal policies may have begun to factor into planning decisions, but it’s still too early to tell what the impacts of the April 2nd announcements will be. In March, the Dodge Momentum Index pulled back by 7% from February levels.

For 2025, the dollar value of total construction starts will climb 7.5% to $1.26 trillion, down from the previously assumed $1.28 trillion. Nonbuilding starts will lead the way with 10% growth over the year, following stronger demand for streets and electric utilities.

Nonresidential starts will expand by 7%, driven by strength in data center construction, megaproject construction on the institutional side, and more renovation activity. Retail stores, warehouses, office buildings and hotels are the most vulnerable to a pullback in consumer demand, more selective lending standards, and higher material costs. These sectors are facing the most near-term risk. While total dollar value was downgraded by only 1% from last quarter, our outlook our square-footage forecast was downgraded from 5% growth in 2025 to a pullback of 1% in 2025 for nonresidential construction.

Residential construction will expand by 1% in unit terms. We have revised multifamily construction down from 9% to 5%, and single-family construction down from 3% growth to a 2% decline. The near-term uncertainty is more likely to cause homebuyers to remain on the sidelines and hold on to their savings, while homebuilders simultaneously face higher material costs and further labor constraints.

Manufacturing construction will also face sharp declines this year, following the 50% decline it’s already experienced in the first three months of the year. Given the anemic start to the year we have revised our dollar value forecast from a 1% decline to a 16% decline for the year. Though there may be some upside potential in onshoring and reshoring manufacturing activity back to the United States in the longer term, it is unlikely to correlate to stronger construction over the next 3-5 years. The current levels of uncertainty around domestic and foreign policy make it difficult for firms to invest in projects that cost millions to billions of dollars and take several years to complete. In addition, demand for those manufactured goods is at risk as consumers remain sensitive to price increases. Unless tariffs are offset with policies that provide longer-term incentives for these producers, tariffs alone are unlikely to result in significant onshoring over the next five years.